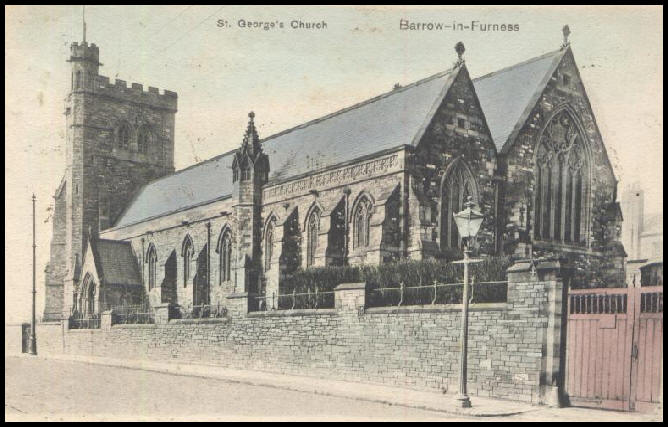

I wanted to give historical writing a try while I was studying for my MA. I used this chapter in a conference. It is only a chapter… It’s not from anything I’ve written since, but I just wanted to get a feel for how historical fiction might be to write. Rabbit Hill and Gradwell exist, of course- you will know this, if you are local to Barrow, and this scene might well have happened right on the cusp of the industrialisation of our area…what do you think? (Photo courtesy of Furness Family History Society)

Rabbit Hill by Paula J. Hillman

Salthouse

Winter 1866

Red mud and loneliness: these things have become Finn’s parents as surely as Mammy and Da back home. They too were muck-ridden and solitary. He’d loitered in the middle of a family the size of a small tribe, wanting to learn reading and writing when all the longing got him was a slap. Finn toes the floor under his bunk. How he’s supposed to do what Gaffer Doherty says and smarten up, is a mystery. He is what he is: a full-grown boy from West Cork, scared enough to run.

There’s a damp chill pushing under the door of the hut this morning. It carries with it the scent of the estuary: salt water, and the green seaweed that hadn’t existed back home. This stuff floats on the surface and tracks the movement of the waves. When he’d first seen it, the texture caused a grip to his stomach enough to make him spew. It feels more normal now, though he can never bring himself to eat it like some of the other navvies: Keeps yer regular, is what they tell him as the weed is added to the cookpots. His portion, he eats clean.

Outside, some others are already about their business, caps pulled down, pipe stems stuck between their lips. And cleaning out boot treads on their pick-axe points. Finn slaps across the wet mud to join them.

‘Here’s me’laddo.’ The shout goes up; one that always gets him a ribbing. That he’s to return the jibe in some way, he understands. But he’s freezing today, with a belly as empty as the pockets of his coat, and empty of humour too. No moleskin for him though, he makes do with an oil-slicker, and there isn’t warmth in that. For a moment, he’s stuck for something entertaining to say. Then it comes.

‘T’is a grand day.’ Eyes to the sky. ‘For licking the arses of Gradwell and his cronies.’

A roar of laughter. Finn might not be top-grade on the tools, but he knows how to use his words.

‘Just you keep that gob of yours shut when yer man’s here,’ says Dove, of the iron-grey hair and feather-soft voice. ‘We don’t want him reporting back, so we don’t.’

More heaving of boots on metal and the smell of fried bacon. Finn’s stomach flips over. Two lots of meat a day is making him grow tall and lanky. The back-home potatoes had cramped him, in more ways than one. But he knows better than to keep carping about the past. The men don’t like anything but hard-graft and gruesome stories. They’re not for putting up with moaners. When he’d left Skibbereen, more than three years ago, it wasn’t Mammy and Da he’d missed, or his wee brothers and sisters; that leaving had been easy. No, it was the blue-grey of his coastline and the soft play of a sunlit morning spent bouncing stones; that tugged at the back of his throat and brought tears. Even though he has found himself living near the water’s edge again, it isn’t West Cork, it’s Lancashire and it doesn’t have the same feel. This is the hard green version of Irish Sea, with its cutting wind and its gloom. So he does as Dove suggests, keeps his head down, arse clean and eyes front.

A growling moan cuts across his thoughts.

‘I need some feckin’ breakfast.’ Stone. Staggering from his hut like a bear with a drink problem. ‘Sorry, but I do.’

Finn follows him across the site towards the mess area. Mess is the right word for it. Most of their food and drink comes coated in a layer of red clay. This morning’s bacon is no different but is grabbed and guzzled all the same. A fine rain has started up, coming from a sky that’s flat and silver. He pulls down his cap and rolls his collar. There’s a day of clearance ahead, a hacking away of the gorse and brambles that cover Rabbit Hill, to make it ready for another building, though he’s not sure what, being only involved at the level of brick and stone. None of the brainy men live on his site. Theirs are the better places, further away from the water’s edge. They have proper privies and planking on the floor. And they don’t double up as a storage yard for bricks and timber.

Gaffer Doherty has appeared and is staring at him. The man is small and wiry and lethal. But he’d given Finn a chance. That day, on the dockside, holds one of his worst memories. The heat and the sickness and the longing for a space in the world, and only his fiddle for company. The months working his way across Ireland to make his fare on the steam ferry, left him invisible: there was no other word for it. Standing against the wall and looking at his feet, waiting to die. Then there was Doherty, giving him a ticket and thumbing towards a cart already loaded with other lads like him.

‘O’Brien. Ye great galoot.’ Doherty is coming for him now. ‘Jesus. That soft mug needs a wash. Were you not told of Gradwell’s visit? Will he want to see his brickies covered in filth?’

‘He won’t, sir.’

‘And will he be here any minute?’

‘He will, sir.’

Finn stuffs the rest of his bacon and hard-bread into his mouth and skitters across to the water barrels: washing, drinking, making mortar, it’s all one. Little wonder all the men have had the wild shites at some point. There’s no scum on the surface this morning, but it’s freezing just the same. As he’s splashing and wiping, the shout goes up: Gradwell’s Brougham has arrived.

‘Jesus, fuck,’ he hears one of the men say. ‘What happened to using yer legs.’

Then the air is full of horse’s breath and whinnying, and Finn can only stare as a huge man heaves himself out of the carriage door and coughs loudly. But there is someone climbing out behind him. A young woman; a girl, really. As tiny as the man is large, with a face like none Finn has ever seen. It’s a pale oval, the colour of cream and looking as soft. His mammy would sometimes let him dip a finger in the same liquid, just before she churned it to the buttery stuff they sold to better-off families. But that was when they’d had the full farm. A time he can hardly remember, save for the small pictures that sometimes come to him, waiting for him to add words.

Across the site, men are lining up, shoulder-to-shoulder and huffing into the raw morning air. Gradwell, all silver hair and mutton-chop-sides, is reaching down to shake the hand of Gaffer Doherty. Finn can see embarrassment in the way the girl is smoothing her dress. The colour of it reminds him of the sea on a stormy day, and it shimmers as she moves. There is a twitch in his fingers, he wants so much to join her in the smoothing. But she doesn’t see him. If she even looked, she wouldn’t see him. And now she is stepping away, past the men, with no care for the mud or the toes of her boots. Gradwell is deep in conversation and hardly seems to notice. Something is going on that’s not right, and it makes Finn shudder. That girls come onto the site he knows only too well; the men bring them back, late into the night. Not girls like this one, though. And now she’s got away from them all and is wandering towards the far side of the site, dress hem clutched in her hand and peering into the doorways of huts.

Gradwell’s attention finally turns.

‘Alice,’ he roars. They all start. ‘Alice Gradwell. Girl. Get back here.’

She tilts her head towards him and waves a small hand. Finn thinks his legs might collapse beneath him. There must be a strength to her, that she can deflect the older man with a simple gesture. Gradwell harrumphs but makes no move to follow her. Instead, he resumes his conversation with the gaffer, all the while watching the girl’s wanderings from beneath one cocked and bushy brow.

Amongst the men there is an atmosphere of unease. None can go about their business with this imposter on the site; they are becoming cold, edgy. Breath steams and spittle is hawked. Finn experiences a flash of alarm. The girl is dangerously near a brick stack that he knows is precarious; timbers lean in a way that makes their removal easy. But a touch in the wrong place could scatter them all. No one is watching. Only him. There is conversation. Finn can make out some of the words –bunks, rot, scything– and gestures that seem to be pointing up at Rabbit Hill. Dove digs an elbow into his ribs.

‘Don’t be looking at the lassie,’ he hisses. ‘Gradwell’ll have your balls, so he will.’

But Finn can’t help himself. And now she is making her way towards the scrubby land at the edge of the site. The place where water leaves a slick of brown foam and rope scraps. Not somewhere a girl like her should be, that’s for sure.

‘I’m not liking it.’ A fierce shake of his head. ‘I’ve a mind to go down and bring her back.’

‘You will not.’ Dove’s last word stretches into a quiet growl.

‘Sure, and when that one slips, or the stack falls, then what?’

Dove turns away from him and shoves his hands in the pockets of his jacket. He is saturated with rain now; they all are. Gradwell and the gaffer are still deep in conversation. Finn wants nothing more than to give them a shout, to ask about why the girl-woman is being given free rein on their site. Instead, he swallows down the choke of his anger and shows his dissent by turning a shoulder away from the line-up and keeping the timber stack in his sight.

A few more minutes pass, and Gradwell’s pair of horses start to paw at the muddy track, snorting and shaking the wet rope of their manes. His attention is grabbed. Something is whispered in Gaffer Doherty’s ear. Then the applause starts up. That he’d better join in is something Finn understands but can’t bring himself to do. It gives a pause in the tension of the line-up, and he uses the chance to sidle away.

Then he sees her again. And she’s kicking at the stack. It shifts slightly, then begins to slip. Finn can only think to run. He needs to cross the fifty yards before another second passes. That way, he can save her. But he’s only half-way there when the first plank comes down on her. Forty yards when the second one comes and she’s on the floor. When the third comes away, he’s there and under it, letting his broad back take the strain and grabbing the fallen girl by the waist. She is feather-light but solid. Her eyes are closed, blood pools in her split top lip. The roar of male voices is filtering through the rain, but he doesn’t look up, only half lifts the girl away as the fourth plank topples. When the rest of the stack falls, she is clear. As he leans over, wondering what he’s gotten himself into, her eyelids flicker. There’s mud in her hair and smeared across the clean white of her cheek. Against his ribs, Finn feels the hammer of his heart. No words come. He’s never spoken to anyone who wears silk and ribbons. Her eyes open and lock with his for the shortest moment, then the screaming begins.

Leave a comment